Circular business models have a different risk and return profile than current (linear) models. Companies and financiers will have to take this into account. Important differences concern the change in financial flows, the dependence on partners and customers, and the complexity of risks.

By explicitly taking this different risk profile into account in the business model and in financing applications, entrepreneurs increase the chance of healthy growth and obtaining financing. This is all the more important because financial institutions have less experience with circular business models and their collateral and risks. Because of this lack of knowledge and experience, financial institutions are more likely to regard circular businesses as risky (Achterberg & Van Tilburg, 2016). In order to increase the chance of obtaining financing and appropriate conditions, it is advisable to take account of this when drawing up the business plan and financing applications:

- Financial flows that change

- Dependence that increases

- Risks that become more complex

Financial flows that change

Generally, circular business models have a longer payback period, requiring more working capital. At the same time, service models often spread potential collateral across more products.

Read more

Cash flows

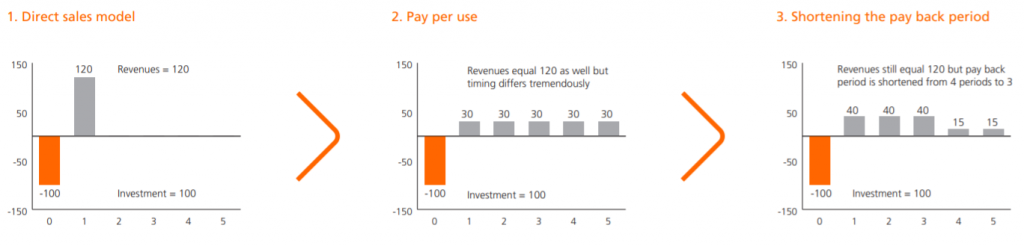

Circular business models often use product-as-a-service models. This changes the nature of cash flows from the transfer of a sum of money at the time of sale to a series of regular payments over the life of the product. In this way, product-as-a-service models create a longer financial relationship between a company and its customer (see figure 1).

Because cash flows are spread over time, the payback period of an investment is longer. A contract with a payback period of three years is less risky for a circular company and a bank than a longer payback period (higher risk of payment arrears). Cash flow optimisation is therefore an integral part of the financing of circular business models.

Figure 1: payback period for different earning models (ING Economics department, 2015, p38).

Working capital

Working capital is needed to buy new assets (e.g. a washing machine) when new service contracts are signed with consumers. However, because a company purchases or produces the assets at the beginning of the service period, long before the sum of the periodic service fees covers the purchase costs, the need for working capital is exceptionally high compared to the traditional buy/sell business model (Working Group FinanCE, 2016, p87).

Collateral

Although we are used to service models for expensive products (e.g. lease cars), in a circular economy all kinds of products are provided as a service. Think of household appliances, clothing or smartphones. These products, unlike cars for example, are less suitable as collateral. On the one hand because of the limited sales value, on the other hand because of the spread of the products (a product in every household) (Achterberg & Van Tilburg, 2016).

Dependence increases

Close cooperation between chain partners also means that if one of the partners is unable to supply, the entire chain will be led by it. In addition, in the case of pay-per-use models, the entrepreneur also becomes more dependent on customers, because they pay longer for a service or even are legal owners.

Read more

Dependence on chain partners

As an entrepreneur, it is impossible to bear the responsibilities for providing a circular service alone. The product is made in a (complex) supply chain and – in the circular case – also (partly) returns to that supply chain. Services such as maintenance, logistics, consumables and data services are usually also offered by third parties. This creates a dependency on these partners, and thus a different way of risk assessment of the financier (Achterberg and Van Tilburg, 2016).

Creditworthiness of customers

Circular earning models complicate the creditworthiness of customers. For example, with pay-per-use models, the cash flow to the company is spread over time. As long as these run the risk of bankruptcy of the customer. Since sustainable products usually have a lifespan of several years, this risk cannot be ignored (ING Economics department, 2015, p40).

Shared ownership and responsibility

A real estate owner automatically owns all the earth- and nail-resistant components in a building. If, for example, lighting is built into the ceiling of an office, then it becomes part of the building, so the property owner is also the legal owner of the lighting.

For example, if Philips would like to retain ownership of the lamps in a pay-per-lux model and take responsibility for the lamps and luminaires after the use phase, then ownership is still automatically transferred to the property owner.

Practical solutions are possible. Although legal ownership can be lost, a company can remain economic owner through binding agreements in contracts. However, contracts do not provide a guarantee in the event of the customer’s bankruptcy (ING Economics department, 2015, p39).

Risks become more complex

The pioneering status of circular companies and the increased dependency between chain partners also increase the complexity of business operations. This brings with it accounting and legal challenges and costs.

Read more

High administrative costs

Because the relationship with chain partners and the end users who purchase the product as a service is shaped in contracts, operational and organisational complexity increases, resulting in higher costs for contract management, credit checks, invoices and the tracking and monitoring of (the use of) assets (Achterberg and Van Tilburg, 2016).

Accounting challenges

By offering a product as a service (instead of selling it), the product remains the property of the service provider. These products therefore remain on the balance sheet (assets). This creates a capital need to finance the ownership of these assets and possibly the need for an external financier if the company cannot handle this internally.

In addition, valuing these assets (products) becomes more complex in a circular economy, since it creates residual value (the possibility to offer the product again in a contract) and thus, in principle, never becomes “zero”. In traditional accounting methods, assets are always written down to “zero”. Current accounting rules and ratios are therefore often not appropriate for a circular economy.

A combination of the shift in ownership and the entanglement of responsibility in the chain leads to higher complexity in the estimation of collateral value, which further complicates financing (Working Group FinanCE, 2016, p83).

Legal consequences

Models around products-as-a-service rely on an extensive and long-term contact with customers and include more duties on both sides. The service provider must guarantee the operation of the assets throughout the contract, which may require repair, maintenance and replacement. On the other hand, the end user must use the assets as directed and respect maintenance requirements. The legal risks of these longer relationships increase the operational risk of the service provider(s) (Working Group FinanCE, 2016, p88).

Creditworthiness of entrepreneurs

The creditworthiness of circular companies is more quickly recognised as risky. When a start-up or relatively young SME operates in a circular manner, financial institutions often do not assess them as creditworthy enough. They have a short track record and a limited financial position. In addition, they market existing products in a new way or have developed completely new products.

This is why these circular companies can easily be regarded as risky. Nevertheless, the risk profile of a circular company must be carefully assessed. The estimated risk can partly be explained by a lack of information and the inadequacy of traditional risk models (Working Group FinanCE, 2016, p71).